Consulting isn’t neutral: how professional services are quietly shaping our climate future.

Op-Ed by Kate Melville-Rea

Over dinner recently, a friend who works at one of the Big Four consulting firms confided something that stuck with me. They’d been “on the bench” – corporate jargon for having no client projects and waiting nervously for the next assignment.

“I’ll never work for weapons or gambling… But maybe I’ll have to say yes to coal or gas.”

That one sentence captures a quiet but urgent dilemma inside today’s consulting industry – one that reveals how corporate incentives can override personal ethics.

Consultants, we’re told, have choices. But when those choices risk your job, your promotion, or your visa status, how real are they?

The hidden emissions of consulting

The consulting industry has a hidden carbon footprint – not in its offices, flights, or servers, but in its serviced emissions: the climate impact of advice, modelling and lobbying that enable fossil fuel expansion.

Firms like EY, PwC, KPMG, Deloitte and McKinsey publicly commit to climate leadership, yet continue to serve clients whose business models depend on fossil fuel growth. Their direct emissions may be limited to computers and office lights, but their influence reaches far beyond — shaping government decisions and public narratives in favour of whoever can pay the most, often fossil fuel clients with deep pockets and vested interests.

These serviced emissions are the professional-services equivalent of Scope 3 emissions – the downstream climate impact of what you enable, not just what you consume. And right now, they’re fuelling the crisis far more than any firm’s internal footprint ever could.

Three examples of consulting gone wrong

Take EY. In 2023 it produced modelling for the fossil-fuel lobby group Australian Energy Producers (AEP) that was used to tell the government “independent analysis confirms new gas supply is needed in all net zero pathways” – a claim that flies in the face of international evidence showing we must slash fossil fuel use, not expand it.

KPMG inflated the economic benefits of gas in its 2023 report for the NSW gas industry, overstating job creation and downplaying environmental risks. Their “findings” were amplified across websites, billboards, and government submissions used to influence policy.

And McKinsey recently produced a report for the Business Council of Australia outlining scenarios that placed Australia’s 2035 climate target between 50 and 70 percent – all below the scientific floor of the 75 percent cut needed to keep the Paris goals within reach.

EY didn’t drill the well. KPMG didn’t lay the pipeline. McKinsey didn’t legislate a weak target. But their work helped justify all three – through one-sided analysis, polished spin, and a veneer of independence. These aren’t emissions you’ll find in a sustainability report, but they are real, measurable, and mounting.

A framework for accountability

So how do we assess and avoid serviced emissions in practice? It starts with asking two simple questions:

Is the client aligned with climate goals?

Is the project aligned with climate goals?

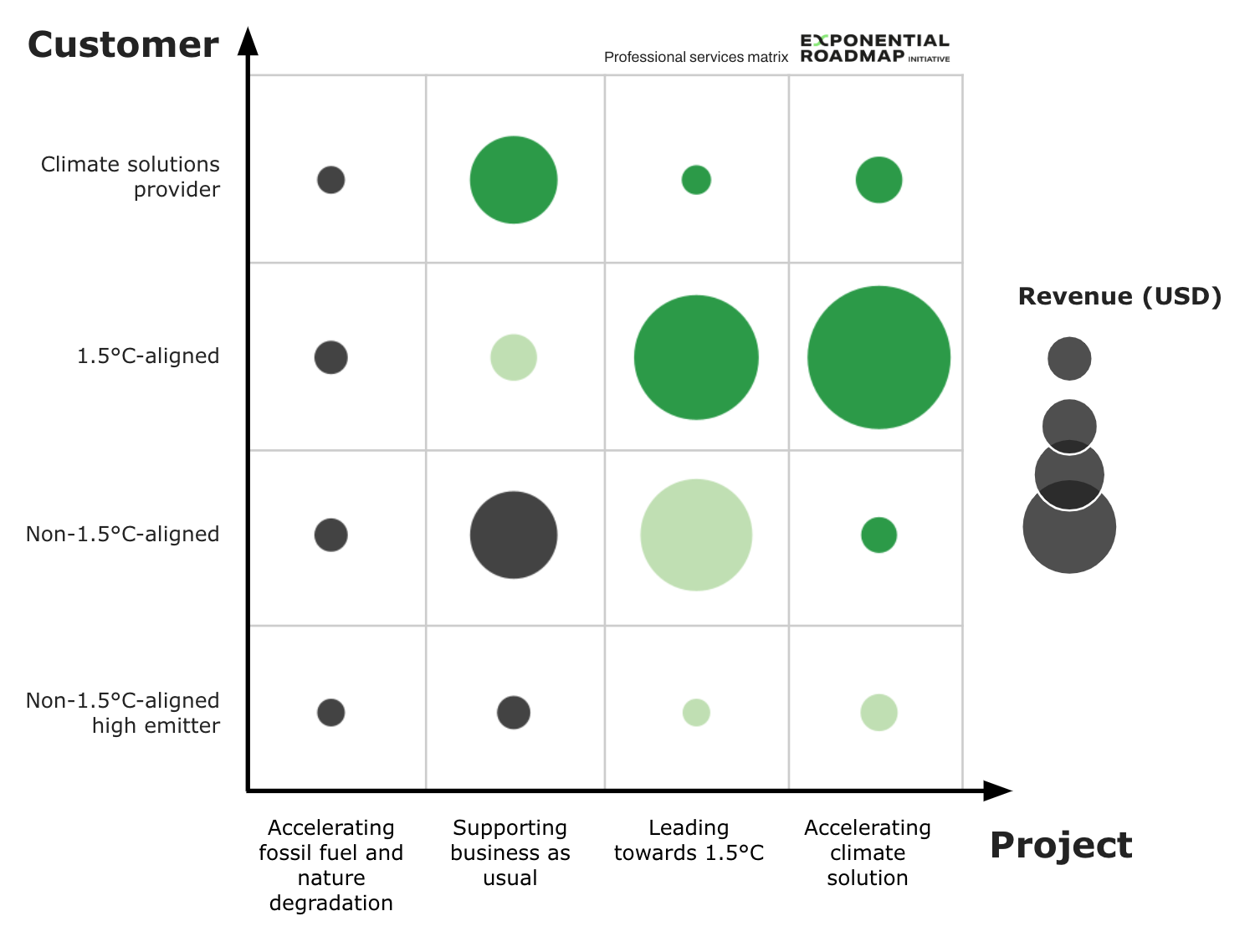

Together, these form a Professional Services Matrix, developed by Oxford Net Zero and Exponential Roadmap – a simple but powerful tool to assess whether a firm’s work is helping or harming.

Professional Services Matrix example by Exponential Roadmap. The top right corner is where we want to be: good clients, doing good work. The bottom left is what we must avoid: harmful clients, commissioning harmful work. Everything in between deserves scrutiny.

That’s the clarity staff deserve, and the transparency the public, investors and regulators need. There’s no reason this isn’t already standard practice. In fact, it’s shocking that it isn’t.

Time to move the moral burden upstream

No junior analyst should be expected to push back on a fossil-fuel engagement when their job, promotion or visa is on the line. Ethical frameworks need to be embedded into the fabric of how consultancies operate – guiding who they work for, what projects they accept, and how impact is measured.

Consulting firms must own their role – and their responsibility. They are not neutral facilitators. They are participants in shaping the future. That means more transparency, clearer rules about the work they take on, and alignment with international climate commitments, including the Paris Agreement, which requires rapid, deep emissions cuts this decade.

Because let’s be honest: flashy sustainability reports don’t mean much when the same firm is quietly helping greenlight fossil fuel expansion.

You can’t claim neutrality when the house is on fire.

Consulting isn’t neutral. Whether you’re drafting strategy for a gas company, building models to support new coal mines, or advising on how to rebrand gambling as “entertainment,” your work has consequences.

No consultant should be forced to choose between their ethics and their career. If firms want to be taken seriously as climate leaders, they need to remove that burden from staff by setting clear rules on who they work for and what kind of projects they accept.

The fork in the road is here. Consultancies can either keep enabling fossil fuel expansion, or they can stand by their climate commitments and help deliver a real transition. They can’t do both – and time is up for pretending otherwise.